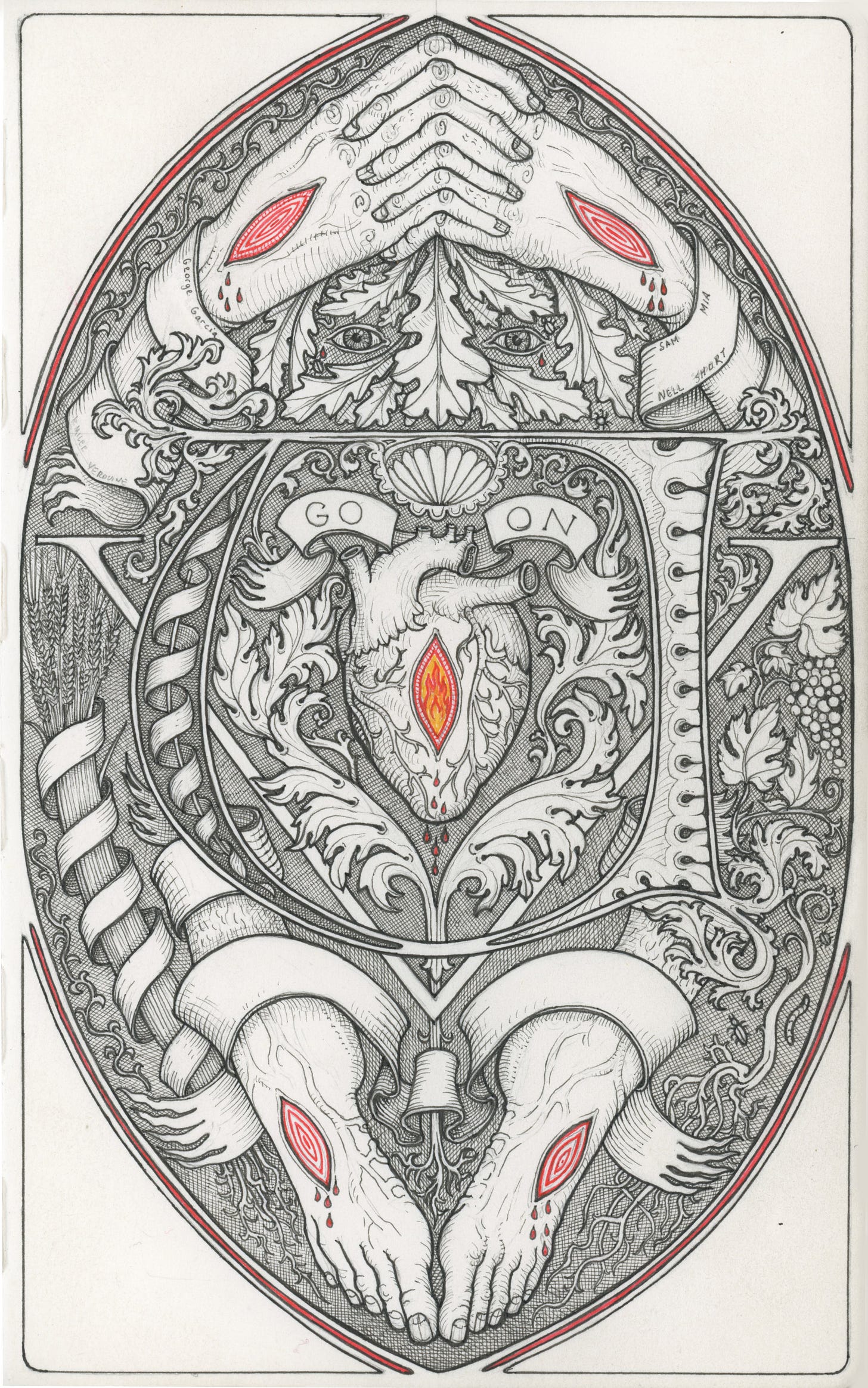

When Jack Baumgartner shared his drawing “Go on, Wounded Healer,” he confessed: “There may be so much I would want to say about this drawing that I must therefore say nothing. Breathing and silence.” This drawing is from a collection of drawings titled “The Diary of a Tree Standing on Its Head.” He also wrote beneath the original pencil sketch, “The wound and the five wounds.”

Although Jack is probably wiser than me not to talk about this drawing, I’d like to risk telling you what I see. I don’t pretend to see as deeply as Jack, or even as deeply as you can see, but I humbly offer the limits of what I can see. As I’ll share later, I have a personal connection to this drawing, which makes it even more meaningful.

The Five Wounds of St. Francis

While St. Francis was praying on a feast day of the cross around the year 1224, a seraph appeared to him. Then five wounds began to form on St. Francis in his hands, feet, and side. They were elongated circles, pinched at the corners, just like in Jack’s drawing. St. Francis was the first recorded person to have borne these marks or stigmata. Stigmata was a Greek word which often described the branding that cattle received from a burning iron. It’s interesting that seraph, a kind of angel, means “burning one.”

Stigmata are a sort of micro-incarnation, in which the fire of God richly participates with the flesh of humanity. St. Francis was not just branded, but he was branded with Christ, as was Christ branded with him. Christ was the fire and Francis was the bush.

Whether we realize it or not, Christ’s incarnation is a reverse stigmata, in which He brands our wounds with His divinity. We inflicted wounds onto Christ; He ‘inflicted’ a new divine nature onto us and our wounds. There is life in His wounds, and He pours His life into our wounds. This drawing will unpack that for us.

It Started with a V

Jack said it all started when he drew the letter V into his diary. Then he began to ‘decorate’ or illuminate the V, much like a Medieval monk might do. The V is the Roman numeral 5, which stands for the five wounds of Christ. So, right away, metaphorical layers begin to appear. It’s not just a V, but a five; it’s not just a five, but the wounds of Christ; it’s not just the wounds of Christ, but stigmata on us; and it’s not just stigmata on us, but His wounds on our wounds.

One Wound and Five Wounds

You may notice the five wounds: one in each hand, one in each foot, and one in the heart, which is in the middle. But the five wounds are within one larger wound, which makes up the circumference of the entire drawing. Each of the wounds are outlined with red; in fact, the four ‘little wounds’ contain multiple concentric wounds, producing a mesmerizing effect no matter which you look at. Not only did Jack put the five wounds within one large wound, but also he placed several smaller wounds within the little wounds, so that we see it is wounds ‘all the way down.’ Yet, this is not a defeatist manifesto, but, as we will see, the engine of new life.

The Letters

Clearly Jack put letters within this drawing, but what’s striking is that not all the banners contain a message. Some of the banners, such as the ones emanating from the hands and feet, are ‘silent’ messages. Perhaps, since they are so close to the hands and feet of Christ, they have been dumbstruck—but in doing so, they are powerful ‘speechless’ speeches.

The other letters seem to be floating about inside the large wound, looking much like the organelles of a single cell from biology class. I mentioned the V already, where it all began—the nucleus, if you will. But overlaid the V, there is a letter that looks like several letters at once: a U, an backwards D, an O, and an upside-down N. Unscrambling these letters and putting them together, you read O-U-N-D, so all that’s missing is the letter W, spelling WOUND. Perhaps the W is found in the shape of the banner draped over the feet. Maybe. But if you take the original V and double it, once for the wounds of Christ and once for our own wounds, you get a double-V, or a W. Our wounds are spelled-out together with His in this drawing.

Vision

There’s another thing I’d like to point out about the five little wounds: each of them is weeping. Jack drew several drops of blood dripping from the corners of each wound, producing the effect of strange blood-tears, which means each little wound is also an eye. And that is a tremendous insight: wounds are a source of vision.

Go back to the concentric circle-wounds once again. Keeping with the theme of vision, the concentric wound-ovals give the impression of a telescope. Just as the tubes of a telescope overlap in order to magnify and focus, so do our wounds give us greater vision. Our wounds are lenses to the unseen and unknown—we see more through our wounds than we could see with the naked eye. God appears closer to us when looked at through the telescope of our wounds.

Eyes

Speaking of eyes, there are two ‘normal’ eyes near the top of the drawing, and they, too, have blood tears dripping from them, but not as dramatic. While this is only a sketch, I believe Jack drew his own eyes here. They are clear and steady, yet hiding. Whomever they belong to, without them, the drawing would feel less personal; but even an abstract piece like this is made personal through the presence of those two eyes.

I see someone hiding inside. In fact, I see our shy God, patiently waiting inside the crude elements of this world. “You hid your face” (Psalm 30:7). He is our humble magician, who knows the tricks he can do, but is not brash to do them. He waits in our wounds like a baby waits in a womb, hands and feet tucked carefully within its soft limitations.

Christ is the Eye within the eye, for, if you turn the drawing sideways, it makes another whole eye. The large wound is also a large eye. The ‘whites’ of the eye are the hands and feet; the pupil is the heart. When God says that you are the apple of His eye, He places your heart right at the center of His own vision.

Fig Leaves

And yet, as I mentioned, our God is somewhat shy. He is not a loud boaster who needs to make himself obvious. Jack drew fig leaves over the face with the eyes, keeping God hidden like Adam and Eve. The fig leaves link the eyes to Adam, Eve, you, and me. In the Garden of Eden, humanity hid because of its shame of sin. In order to recapitulate this eternal moment, we see God haunting all our old hiding spots. You don’t have to hide in your sin and shame alone, but He is in there with you. He is the Face that waits within the darkness. While in the darkness, we think we’re escaping Him; but in the darkness, He is finding us.

Grain and Grapes

The inside of the large wound (or large eye, as you’re meant to see both) is a veritable garden. Not only do fig leaves grow, but also there are grapes and grain. On the left side, there is a sheaf of wheat, or perhaps barley—probably barley, knowing the context of when Jack drew this. On the right side are grape bunches, leaves, and vines. Together, these represent the eucharist, the bread and cup. However, why didn’t Jack just draw already baked bread and fermented wine? Consider, in order to produce the elements of the Lord’s Table, the bread and grapes need to be wounded first. They need to be crushed by feet and winnowed by hands. And the feet that do the crushing and the hands that do the processing are the same ones that have been wounded themselves. What I see is that nobody comes to the Lord’s Table unwounded, including the Lord, who manifests Himself in the wounding and giving of the bread and wine.

The Apostle Paul writes in 2 Corinthians 1:3–6:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of mercies and God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our affliction, so that we may be able to comfort those who are in any affliction, with the comfort with which we ourselves are comforted by God. For as we share abundantly in Christ’s sufferings, so through Christ we share abundantly in comfort too. If we are afflicted, it is for your comfort and salvation; and if we are comforted, it is for your comfort, which you experience when you patiently endure the same sufferings that we suffer.

God puts fresh grain and grapes in the hands of the wounded healer, and the wounded healer is the one who processes them and gives them to others in the form of bread and wine. We bring a dish to the Lord’s Table, as well, and we invite others to table fellowship with God. The wounded healer allures by the fragrance of his or her own suffering.

Shell Cup

Do you see the white shell beneath the eyes? It looks like either a flower or a seashell. I see it as a cup seashell, which is appropriate given its location. The cup is over the mouth. Christ’s own words haunt this image, “Are you able to drink the cup that I am to drink?” His disciples responded, “We are able” (Matt. 20:22). On the one hand, it shows that the cup is for all of us: Jesus drinks the cup of God’s wrath, and we drink the cup in remembrance of His sacrifice. But on the other hand, given the disciples’ hasty response to Jesus of being able to drink the cup as he did, the shell over the mouth in this picture gives the impression of silencing such nonsense. Think before you speak—think before you drink. After all, the cup as a seashell points to the ocean, as if to say that Christ imbibed an ocean of judgment and wrath for us, which is something we could never do.

Heart

Now let’s go below the shell to the heart. I have to say, the heart is utterly stunning. Why isn’t the heart the usual spadelike valentine’s graphic? Why is it realistic? Because this image is not mere symbolism, as symbolism is popularly understood. A mere symbol would distance us from our own selves and the divine work happening in our very own bodies. The trouble with the usual heart ‘love’ symbol is that it gives the impression that God’s love and work are only for the proper and tidy. By drawing a realistic heart, Jack drives home the message that God’s love and care are for anyone—for the normal, for the messy, for the cut-off, for the bleeding, for the wounded. The realistic heart proclaims to us that our humble bodies, our flesh and bone, are the place where the miracles happen. Do you see what I mean?

As Jack likes to say, nobody takes literalism far enough. We all stop short. We don’t actually believe that our bodies are good, that God became a human, that each heart cell dances with life. We back-off and swap-out sentimental symbolism, fantasies for the real thing, emojis for raw emotion. But the realistic heart sends the clear message that you are good, loved, and beautiful, just how you are. God wasn’t playing games when He made us, this dull flesh and these humping organs truly image-forth their Creator.

Also, can you see the fire in the center of the heart? It is lined with bricks, making it a furnace within the heart. I know Jack is fond of the book of Daniel, so right away I thought of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego in the fiery furnace. Then a fourth shows up with them, God Himself. Just as God is in our hearts, He is in the furnace with us. Our hearts are aflame with love for Him, even as He is there with us, kindling the flames.

But what about the severed blood vessels on the top of the heart? On the top left is the aorta, which sends oxygen-rich blood to the whole body. Think of it as ‘Spirit-rich’ blood. On the top right is the pulmonary artery, which sends oxygen-poor blood to the lungs in order to be replenished. At work in your heart are life and death. And this is no mere metaphor! Your heart is participating in life and death all the time, as you inhale and exhale. Your heart is proclaiming to you what this entire wound is doing: leveraging death in order to kindle life. This is the cycle at the center of us all, and how God uses wounds to generate new life and possibilities. In fact, the fire in the center cannot burn without the aorta and artery regulating the oxygen levels.

There is also blood dripping from the heart. Similar drops of blood are coming from each of the five wounds. To me, these blood drops also look like seeds. Wounds produce the seeds of new life.

Roots and Pronounced Veins

Keeping with the theme of seeds, notice all the roots in the picture. While you’re at it, notice the veins similarly spiraling on the feet. We are meant to see them as the same: feet-roots and root-veins. These are the channels through which blood-sap travels. Again, this wound is a living organism, more like a human cell, filled with organelles and brimming with activity. Something is happening in here! It is not death, but life and potential. Something wonderful wants to grow. The power of this drawing is that when you close your eyes and imagine your wound, whatever it may be, you now have permission to see it as a living-wound.

Banners with Fingers

Now look at how the feet and hands turn into banners. This is an incredible understanding of the connection between ‘word’ and ‘flesh,’ heaven and earth. Jack often makes banners with messages, but the banners on the hands and feet do not have obvious words; instead, they transform into action. As the messages unfold, they become hands and feet. These are not sterile words, sterile seeds, or sterile messages; rather, they will accomplish what they say they will do. They will not return void, but will bear fruit. God’s words to us are as good as done; and God’s deeds to us are as good as any message to us. If God has provided for you from His hands, the message is a loud-and-clear “I love you.” And if God tells you that He loves you, then He will back it up with real-life action. God will accomplish His word. In fact, look at the frays on the ends of the banners, don’t they look like fingers and toes?

Names

Sticking with the banners, there are some faint, secret words on them—some precious, hidden names. I’ll let your eyes wander around the banners in order to discover them. These are the names of some people that were on Jack’s heart when he drew this. He incorporated them into the drawing as a prayer.

I’ll point out one name. Mia was my next door neighbor. At just seven years old, she suddenly passed away in November. After she initially went into the hospital, I told Jack about her and he began to pray, which led him to write her on these banners.

Each name on these banners, draped around the pierced hands of Jesus, buried within this large wound, surrounded by vegetation and life, made to look like both an eye and a seed, participates in the work of the cross. All of these things are the gears of the cross as the energy of God is transferred to us. These names will not be lost, but they are being planted, watered, and unfurled. They are being made a part of the fabric of reality, as they are among the organelles of this single potent cell of life. Their lives are the DNA of all life, you could say.

God says to His people “I have engraved you on the palms of my hands” (Isa. 49:16). The word “engraved” means to pierce the skin with ink. God has tattooed us on his hands, his pierced flesh has metamorphosized into our pierced names, an indelible gesture of His love for us.

Folded Hands

The banners with the names are on folded hands. Why are they folded? And why are they on the top of the unseen head? I see a person praying, whose fingers are entwined in perfect symmetry. They are not conflicted, in other words. The right hand knows exactly what the left is doing. They are united in their pursuit of God, they are in prayer so they are at peace.

The sight of folded hands in the context of much wounding is a great source of comfort. The hands are not contorted in agony, such as are the hands of Christ in Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece; rather, they are perfectly alighted and resting in the hope of the promise of the glory of God. Our wounds are ultimately not a source of torture, but God assures us that all wounds work together for the good of those who love Him. We can simply rest our hands and be at peace, knowing that God will take care of us. The seeds of suffering are already sown, we have a Good Farmer, and it is only a matter of time before we get to be a part of the glorious harvest.

The Womb

The heart at the center of the drawing is more than a heart; and the supple slit in the middle of the heart is more than a wound. Notice how the banner with the words “Go on” are in the shape of fallopian tubes with ovaries. This means the heart is more than a heart, but the maternal anatomy of life. I don’t have to get more detailed in order for you to fill in the rest. I’ve been saying it this whole time, but now the message is clear: our wounds are generative. New life comes from our wounds like new life comes from the womb. The message of the fallopian tubes is clear: Go On. Don’t quit, just because you’re hurt. God is doing something new through all the old troubles and pains. This is the very passageway of life. Jack has removed the fig leaves in order to make this message clear.

We rightly refer to the Fatherhood of God, but an image like this reminds us of the Motherhood of God. She is not only the source of new life, but also she is the source of great comfort, care, and nurturance.

Now if you look at the hiding eyes once again, you get the impression that Christ is waiting within the womb to be born. Is it a coffin or a uterus? Is it death or life? Are they drops of blood or seeds? Is it a crematory or a kiln? All of these ambivalent images converge like tectonic plates beneath the surface of reality, ready to shake our foundations straight again.

A Billion Christs

I initially told Jack that I think this is how he sees every seed, and here’s what I mean. In a 2023 lecture, Malcolm Guite reminded us of the way a child sees the world. To the child, the sun is not just a ball of gasses, but it is a personal utterance of God. That’s why every child puts a smile on every sun he or she draws. Or, as C. S. Lewis said, what a thing is made of is different than what a thing is.

It seems to me that Jack, too, puts a ‘smile’ on everything he draws. It is his earnest attempt to show us the meaning of things. This drawing has Jack’s smile written all over it. It is a wound with a smile. It is a seed with a smile. It is tears with a smile. It is drops of blood with a smile. It is an eye with a smile. It is a cell with a smile.

I don’t know if Jack plans on making a woodcarving out of this drawing so that prints could be made, but it would be quite fitting, for this picture is a stamp. This picture is stamped on every cell, eye, drop of blood, tear, seed, and wound that you will ever encounter. You may not be able to see it, but it is there. Over all your wounds is stamped this image that Jack has made. We need to learn to see every atom with new eyes. You could say, there is not just one Christ, but a billion Christs, doing the work of God without rest. In every wound, Christ curls-up in the fetal position, waiting.

Go On, Wounded Healer

I’d like to bring this personal meditation to a close with three quotes. The first is the opening prayer for the festal Mass:

“Lord Jesus Christ, who reproduced in the flesh of the most blessed Francis, the sacred marks of your own sufferings, so that in a world grown cold our hearts might be filled with burning love of you, graciously enable us by his merits and prayers to bear the cross without faltering and to bring forth worthy fruits of penitence: You who are God, living and reigning with God the Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, for ever and ever. Amen.”

I like that it calls the stigmata of St. Francis and the wounds of Christ ‘sacred marks.’ As we’ve seen, God can turn all our wounds into sacred marks. So, I ask, what are your sacred marks?

Next, here are some verses from David in Psalm 30: “Weeping may tarry for the night, but joy comes with the morning” and “You have turned for me my mourning into dancing” (5, 11). The message is clear: Go on, Wounded Healer—keep mourning, and keep dancing.

And finally, here is a poem I wrote after a long reflection on Jack’s drawing. Although I hesitate to include it alongside such a profound piece of art, Jack would be the first to tell me that my words are important, too. So, here’s my new poem “Wound.” This is for Jack.

"Wound" When I see wound, I also see wound. Like the wound gears of a clock, Or the golden gears of St. Bede's Box. But the Craftsman does not set it aside, Instead the Maker steps inside. He folds his arms and legs in place. He puts the fig leaves over his face. Out from the darkness you hear him sing, While he leans on the gears of suffering. The spiritual mechanics of every wound, Are calibrated by the Virgin’s womb. And all the things that cause us sorrow, Breed immortal what they only borrow.